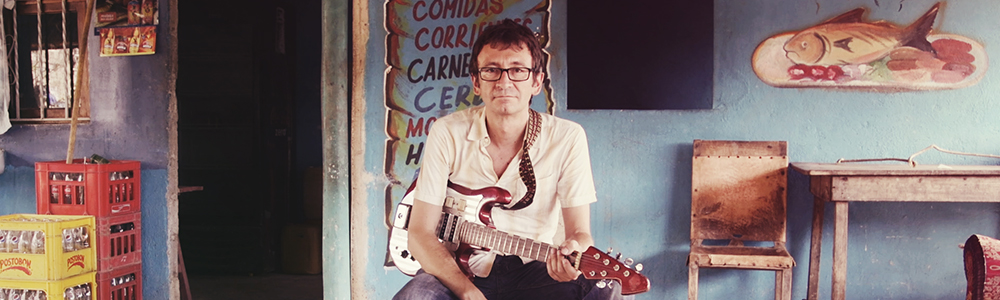

Well, some of them had a mic input in that shiny metal faceplate. When Roberto Lopez was a teenager growing up in Bogotá, he would plug his black Les Paul knockoff guitar into his parents stereo and crank it up until he got that sweet distortion that he was after. Much to his parents’ dismay of course.

When the Montreal-based guitarist set out to make his new album, Criollo Electrik, he went searching for that childhood sound. “I was a big fan of the boogaloo growing up – you know, this mix of Motown, soul, and Latin grooves”, Lopez explains. “With this album I wanted to come back to my roots, to that kid putting his dad’s stereo into overdrive. ”

If music is a language, forget Rock en Español, Lopez has conjured up his own Esperanto — a deconstruction of influence to create something absolutely new. He’s not interested in tumbling down any statues, he’s building a new one right next to them.

Cause this isn’t fusion, nothing so vainglorious as that. This is sunlight filtering through Colombian palms making patterns on some sticky Canadian sugar shack where the wolves are at the door and you gotta run like hell. Roberto Lopez is a bell-ringing dream of tomorrow, but still with the stains of Bogotà bus floors on his Doc Martens, and some heavy metal leather vested hands-up sweaty mess screaming his way to being a hero. You want to mix it up more? Get a Brazilian to play your Colombian rhythms, an African to be your rock drummer. And just when you think you’ve pinned down that image, here comes some long-limbed Nigerian princess shaking her disco booty at you and wagging her finger cause you’ve been naughty, you’ve been using that fusion word, you been keeping it all in your head like some marble statue when the universe is contained down there, and we don’t have any more time for that bullshit. Clik play now!

…but the finished product is perhaps Lopez’ most forward-thinking music to date. Aptly named, Criollo Electrik is an electrified – and electrifying – creole, a musical language of mixed ancestry. With a Brazilian percussionist and an Ivorian drummer playing percussive parts written by a Colombian, it seems only appropriate that this electric creole was recorded in the bilingual melting pot of Montreal. The record is infused with the flavours of champeta, the Colombian take on African music which spread through the picó, or the Colombian sound system. Lesser known than its Jamaican counterpart – but just as vital to street culture and a link to heritage – the brightly painted picos were at the heart of working class parties where, in the 70s, the DJs spun rare records from the Caribbean along with soukous, Afrobeat, and highlife LPs imported from West Africa.